Different Aspects of My Research

Since my early childhood days, I have been deeply fascinated by nature. It has been a source of imagination and inspiration. I would read, write notes, and recite poems on nature and wildlife. This is probably a reason I choose to study biology over other subjects, carry out conservation activities for the endangered species and eventually become a wildlife conservation biologist. Credit goes to my parents for raising me very close to nature, which probably contributed to my passion and love for nature and wildlife. I also rejoice in the society I was brought up with, that had great reverence and admiration to every element of nature; be it a forest, a tree, a bird, a tiger, a lake, or a mountain. Our people always worshiped and protected nature and the environment unconditionally.

I have been actively involved in conservation education and research especially for the protection of the remaining population of the world’s rarest ardeid: White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) which is a critically endangered bird species listed by the IUCN. My latest work in the field of conservation science and ecology was on, “Environmental and Ecological Factors Affecting the Foraging Activity Patterns of the Critically Endangered, White-bellied Heron in Bhutan” which was also my master’s degree thesis. Continuous monitoring and observation of the White-bellied Herons (WBH) in the field had enabled me to learn about their basic biology and ecology.

I continue to devote quality time in exploring and carrying out scientific studies on other unexplored aspects of White-bellied Heron’s ecology and biology, and other globally threatened birds that are at the brink of extinction.

I am an active member of IUCN’s heron specialist group and White-bellied Heron (WBH) working group. I am also a member of the Royal Society for Protection of Nature, Bhutan Ecological Society, and Bhutan Birdlife Society. During my freshman year, I was also an active member of the Nature Conservation Society (Singye Karm), and Sherubtse Green Bhutan.

I have been actively involved in conservation and research then especially for the protection of the remaining population of the world’s rarest ardeid: White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) which is a critically endangered bird species listed by the IUCN. My latest work in the field of conservation science and ecology was on, “Environmental and Ecological Factors Affecting the Foraging Activity Patterns of the Critically Endangered White-bellied Herons in Bhutan” which was also my master’s degree thesis.

White-bellied Heron (hereafter known as WBH) is classified as critically endangered bird species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) owing to its very small population size and declining population trend (IUCN, 2017). WBH is still considered as the rarest heron on earth (Guinness World Records, 2017) and world's most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species (Zoological Society of London, 2014).

An adult White-bellied Heron spotted in Punatsangchhu Basin

Before 1900s breeding success of the bird was mostly attributed to availability of the food (Birkhead et al. 2014). It was only later that the studies on the nesting predation proved significant for the nesting success as well. Study in other bird species such as passerines suggests that nest predation is the major cause of the nest failure (DeGregorio et al. 2014). Nest predators are attributed to be a major risk for the extinction of the native bird species (Innes et al. 2010). Thus, management of the nest predators has proved to an effective strategy to increase the nesting success of the birds (Tapper et al. 1996; Innes et al. 1999; Jones et al. 2005; Starling Windhof et al. 2011; Remeš et al. 2012).

White-bellied Herons are both a riverine and terrestrial species in its mode of habitat use. It forages in the water bodies comprising typically of sand bars and pebbles spending most of its active hours, feeding on fishes (RSPN, 2011). It relies on the subtropical forest with chir pines (Pinus roxburghii) as a dominant species for perching and its nesting habitat. The nests of White-bellied Herons were recorded from Bhutan from an altitudinal gradient of 500-1500m a.s.l (above sea level) (Pradhan, 2007).

It faces continues threats caused by both anthropogenic as well as natural factors. Rapid degradation of forests and wetlands which are the primary habitats of WBH, direct exploitation and pro developmental ventures such as hydro power construction and mining activities (WWF, 2017; BirdLife International, 2018; Dema et al., 2018) causes grave threats to their survival across the range countries.

The paucity of valuable biological and ecological information had immensely challenged conservation efforts of this species (Price and Goodman, 2015). Much less was known about the foraging ecology of White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) compared to other species of same genus before we conducted our rigorous study of the White-bellied Heron.

Foraging ecology of the White-bellied Herons

We continue to monitor the foraging ecology in Bhutan. While we have been able to glean valuable information on the type of prey, prey abundance, effect of microhabitat types and time of the day on their foraging behavior, there is still lack of information related to difference in age related foraging behavior, threats to their foraging habitat, etc.

Foraging activity of the herons are an essential daily activity of all birds for their survival and reproduction (Hafner et al., 1993; Frederick and Spalding, 1994; Papakostas et al., 2005). It's an instinctual habit for all birds to search for food for survival and raise their young (Renken et al., 2016). The ability to forage efficiently in wading birds such as herons had been affected by its own morphological features and behavioral strategies that plays crucial role in fulfilling the dietary needs of individual organism (Breed and Moore, 2016). It has direct relation to how it controls the population trends (Choi and Yoo, 2011).

Through our constant observation, we have found out that one of the parents continues to feed the juveniles in the ground. However, with more days of observation we noticed that parents tend to feeding the weakest juvenile while other active and potential healthy juveniles were seen finding their own food. During the breeding seasons, a family of WBH congregate in the same foraging spot. Juveniles were also observed to night roost in the same tree since our last find. One of the juveniles night roost separately while the parents roost separately from their juveniles as well. During the monsoon when the rivers swell and become murkier, they often shifts their foraging ground towards the smaller streams.

Numerous feeding bouts had been videoed for later analysis as usual. Since the Heron which had been foraging some 100 m below the highway which I must say is the closest so far being spotted and seems to be bit tolerant to human disturbances, we have been able to confirm the prey species being ingested. Later our prey sampling also confirmed the only species found in that micro-habitat was snow trout.

A WBH foraging in the riffles Our attempt to fixing camera traps on the roosting tree

Feathers collected from its night roosts

Snow trout (Schizothorax richardsonii) a known species of prey taken by WBH.

A view of the recently found foraging ground of the WBH

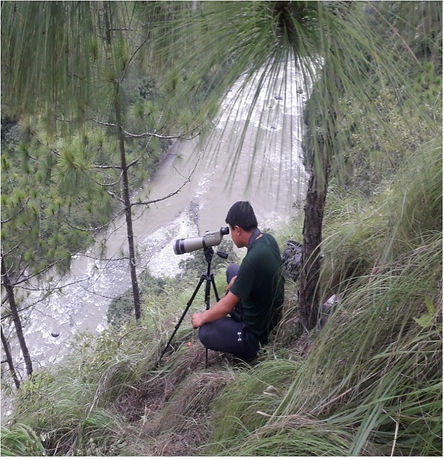

I and Sonam, making daily observation from a strategic point.

We prepared good blind to prevent the bird from knowing our presence and cause further disturbance. It was a successful one. Overall, breeding season is the best time to keep tracking the WBH visually. We observed that the parent keep feeding the juvenile even they have left the nest. We also observed that the parent fly to the smaller stream to derive its feed for the young ones.

Fish sampling had resulted to enlisting of about 17 various species. We sampled 3 small streams divided into 5 zones. These streams had been observed to be visited by the WBH in the past. We could not sample Nangzhina river which is the least disturbed stream and WBH mostly seen visiting the area. This is due to long and very difficult terrain to reach there. It would take at least 4 days journey by walk to reach there. But in the coming future, we will make an attempt to visit there at least once. The most abundant and common fishes found were Neolissochilus hexagonolepsis (Copper Masheer),Schizothorax richardsonii (Snow trout) and Gara sp. Few species of fishes had been yet to be identified.

Fish sampling team at Burichu upstream.

We could observe WBH at Phochu, but due to human disturbances (Children playing near the riverbank, rafting, human settlement near the river, we could observe the WBH being stressed out. As heron was observed to be perching on a pine tree for almost nine hours without feeding. We found this to be an unusual behavior. Later it made a high flight which could only mean long distance flight and it would take some time to return to the same area back. We returned to Burichu and spotted the Heron and its night roost. We also collected the fecal and feather samples.

WBH roosting in Phochu.

A WBH with its prey (Schizothorax sp.).

Night Roosting Behavior

Night roosting behavior bears significance for the natural history understanding of the diurnal species and conservation of the threatened species. Like their foraging and breeding sites, night roosting sites are an important factor driving their population dynamics and ecology.

The camera traps were set to find more insights to how they behave in the night and what are the activities they involve themselves in the night roosting tree. The time lapse video and image monitoring of the night roosting behavior have been very successful for trapping their activity every 30 minutes. I have found some pretty good information. This will an additional data to what we have already got from the Zhemgang. Additionally, we also got numerous feathers and fecal samples from this region. With samples from the Zhemgang we now have a representative sample for the genetic analysis.

The weather continues to warm up escalating the temperature, unpredictable blockages of the roads and landslides caused due to onset of the peak monsoon season, leads to many hindrances to the daily observation of foraging activity of the WBH.

Camera trapped photo of WBH in their night roost.

Nest Predation

Nest predation is likely one of the most important threats causing precipitous decline to the population of the White-bellied Herons in Bhutan and other range countries. While there has been no credible information of nesting predation from other range countries, it seems that the only credible record from Bhutan highlights the need to avert predation risk of this highly threatened species. Every year there is one to two cases of nesting failure from Bhutan out of mere three to four nesting records from the whole country. The cause of the nesting failure is nor properly understood. Also, nest predation is one of the major threats to the survival of the WBH (Price and Goodman, 2015).

Nearly after 70 years, the first nest of the White-bellied Heron was reported from Zawa, Wangduephodrang, Bhutan, in 2003 (RSPN, 2011). They were found the nest exclusively occurred on the chir pine Pinus roxburghii since its first sighting, in 2018 the first successful breeding on the broad-leaved species was reported (Khandu et al. 2020). They prefer tall trees for nesting.

Our study was the first to highlight the potential nesting failure of one of the nests in Bhutan. On 30 June 2018, a nest succumbed to the nest predation from three active nests. This is significant due a smaller number of active nests counts and success rates.

We chose riparian forest which is the mixed vegetation between 50-500m from the nearest river bank falling within the Tsirang district. A distance of ~ 100-800m maintained between two Camera traps. Camera traps were set up in the failed, abandoned natural nests, and artificial nests. Artificial nests were made to resemble like the natural nests as much as possible (Khandu et. al, 2018; awaiting publication). Each nest was baited with 2 chicken egg which is colored light blue to resemble like the WBH's egg and 1 uncolored chicken egg. The camera traps were monitored every two weeks.

Map of the study site.

Since we had been closely following the incubation activity of a pair of White-bellied Heron we could also find out the exact time and the date of the nest failure (12hrs difference between 30 June-01 July). This helped us to investigate the predated nest without any delay. Upon our investigation we found the egg shells scattered on the nesting tree ground. Next day, We also hired a local tree climber to climb up the nesting tree to check for any clue. We found the fecal matter with mostly seeds of the bean size in the nest and few egg shells scattered. We set up a camera trap baited with dyed Chicken egg, the very next day in the predated nest assuming the predator would return to the same nest. We assume Himalayan Palm Civet as the nest predator of the predated nest. We will also carry out DNA analysis of the collected fecal matter to further validate our assumption.

We continue to propose nest predation mitigation interventions by exploring insights into the drivers of nest predation.